Evolution of a Permanent Negro Community in Lansing

By Douglas K. Meyer

Professor Meyer is in the department of geography at Eastern Illinois University

The following was copied from Michigan History Magazine Summer 1971

Much attention has focused on the historical roots and the residential distribution of large Northern Negro ghettoes. However, the origin of permanent black communities and the initial residential patterns in smaller cities remains a neglected field of research. Although migration is not a recent phenomenon, early Negro population movements and residential patterns have escaped public attention until fairly recent times.

Like many other medium-sized cities today, Lansing, the capital of Michigan, has experience since 1940 the impact of large number of Negroes. This population growth from 1,638 in 1940 to about 11,000 in 1969 has been rapid in proportion to the city’s previous Negro population. A black community, however, has always existed, even though its early settlement went virtually unnoticed by whites.

Migration accounted for about 90 percent of Lansing’s pre-World War I Negro population growth. The proportion of black residents born in states other than Michigan fluctuated between 77.8 percent in 1860 and 51.2 percent in 1880. During each census from 1850 to 1894, more blacks declared Michigan as their state of birth than any other state. As a rule these persons were either children, adolescents, or young adults. Consequently, the remaining state of birth data provide a more meaningful picture of the origins and patterns of migration.

The adult Negroes in 1850 came from New York and the Upper South states of Virginia and North Carolina. One could assume that the blacks from New York arrived with the early white settlers, since pioneers from that state predominated in the found of Lansing. In 1860 Michigan’s two sister states to the south, Indiana and Ohio, were the primary birth places of Negroes. Those few blacks who came from the Upper South came from the border states of Virginia and Kentucky. Even though Canada in 1860 supplied 14.8 percent of the black residents, the Canadian blacks did not comprise an important segment of the population, since these individuals were confined to the state reform school.

Most of the population increase in 1870 and 1880 originated from the border states of the Upper South, especially Kentucky and Virginia, New York, Canada, Ohio and Indiana. Those blacks born in Canada consisted primarily of inmates in the state reform school, young single adults who were employed as servants, waiters, laborers, and children. During the 1870’s, for the first time, four adults from Canada established residence in Lansing. Based on their birthplace the assumption could be made that their parents escaped from slavery via the Underground Railroad into Canada before the Civil War. By 1880 an insignificant number of black from the Deep South resided in the capital city.

Only the 1884 and 1894 population schedules of the State of Michigan censuses still exist for Lansing. Their importance lies in the fact that they indicate important Negro migration trends operating during the 1880’s and early 1890’s. The Northern states of New York, Ohio, Indiana, and especially Michigan continued to provide the bulk of Lansing’s Negro migrants. Of Michigan’s two sister states to the south, Ohio provided by far the largest number of black migrants. Yet an important shift in the makeup of the

Negro migrants lies hidden in the figures. In the previous censuses, single persons under the age of nineteen predominated among those from the Northern states, but beginning with the 1880 census and particularly with the 1884 and 1894 censuses a rapid influx of blacks over twenty-one is clearly visible. These adult blacks brought their families to the city, thus creating a stable black community. Today the descendants of some of these families still reside in Lansing. The number of Negro families increased from less than ten in 1870 to over eighty in 1894. Previously, mobility characterized the Negro population.

Cass County, Michigan, contributed the majority of the Negro families who established roots in the capital between 1884 and 1894. This movement from Cass County had begun by 1880 and persisted until after the turn of the century. Michigan did not dominate as the primary place of birth; instead Ohio, Indiana, New York, Canada, and the border states of the Upper South supplied the greatest numbers.

By 1894 few Negroes had migrated from the Deep South; however, Kentucky and Virginia of the Upper South maintained their place as the major contributors of blacks from the South. Although the number of blacks from the South grew each decade from 1860 to 1894, their proportion in the total Negro population declined during the period.

By 1900 a major component of Lansing’s Negro community were of Canadian birth. With each decade since 1860, the number increased so that by 1884 and 1894 their proportion of the total black population had stabilized at about 21 percent. Not counting migration within Michigan, more Negroes immigrated from Canada in 1884 (54) and in 1894 (89) than any other place. Canadian-born black families were arriving in Lansing as early as the 1870s; however, the most increase occurred in the early 1880s. And the majority of the Canadian Negroes were descended from slaves who escaped before 1860 to Canada. Many of the 50,000 Canadian Negroes who generally dwelled within 100 miles of Detroit returned after Appomattox to the United States, particularly to Michigan. Although a number of Canadian black families came directly to Lansing, many others resided elsewhere in Michigan---Cass County and Mecosta County for example---for varying lengths of time before journeying to the capital city.

The black population of the capital declined from 415 in 1894 to 323 in 1900 but increased slightly to 354 in 1910. Some possible reasons for this loss in Negro population might be movement to areas where employment was better, dissatisfaction with Lansing, loss of identity, increasing discrimination, census taking errors and increase of foreign born who took over black jobs. Similarly, the total Negro population in Michigan experienced a very slow rate of growth between 1890 and 1910.

Despite the considerable slower pace of Negro movement to Lansing, the black migration patterns which operated in the last two decades of the nineteenth century persisted until World War I. It seems that the few Negroes who did move to the city in the early 1900s represented either intrastate movement or transfer from Canada. Three factors influence the Negros’ choice of Lansing as their place of residence at the turn of the century: job opportunities, relatives and friends living in Lansing, and central location of the city in the State.

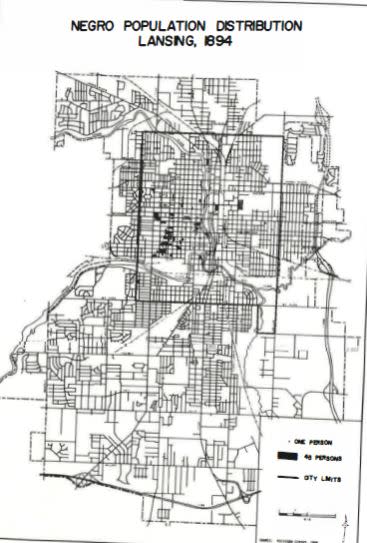

The following map represents black residential patterns which evolved from approximately two decades of permanent occupancy by Nego families in Lansing. An initial clustering of Negro residences appeared along Sycamore south of Washtenaw Street, of which the majority originated from Cass County. Yet the largest number of black households occurred in the block bounded by Butler, Main, Division and Williams streets; most of the inhabitants came from Canada. Domestic servants living with their employers vividly stand out on the map, since only one black resident dwells in a block. Most of the blacks downtown lived at a rooming house on East Allegan Street. The majority of Lansing’s Negroes lived west of the Grand River, with the exception of the thirty-six Negro inmates in the reform school. In addition, a few black resided in the northeast on Turner Street, near East Michigan Avenue east of Pennsylvania Avenue, and south of the Grand and Red Cedar rovers/

As a permanent black community became established between 1870 and 1894, the black residential pattern which evolved primarily consisted of small clusters in racially mixed blocks within an area bounded by Ionia Street on the north, Logan on the east, Isaac Street (now Olds Avenue) on the south, and Townsend Street on the east (map). But an exclusive westside black settlement had not emerged, even though Negroes were not dispersed throughout the city. Instead a few such clusters adequately accommodated most of the Negro population, 415 in 1894.

Prior to World War I, Negro households witnessed few spatial changes from the established residential pattern of 1894. Since Negro migration to Lansing never attained large proportions prior to World War I, both the older Negro residents and the community at large could absorb the new migrants without resorting to residential segregation. Furthermore, most Negro migrants had undergone acculturation to Northern ways of living before arriving in Lansing and no general shortage of housing existed. No restrictions as to location of residence and busin3ss emerged in the city. Consequently, where black residents developed small clusters, these were due chiefly to voluntary actions of Negroes inspired by need to be near relatives, friends, one’s own kind, and work. The clusters were also due to limited incomes and occupational status.

A contemporary author wrote of Lansing’s black community;

As a Whole the coloured people of Lansing are peaceful and industrious, a natural part of the wage-working population. Individuals have become highly prosperous and are much respected.

(Ray S. Baker, Following the Color Line (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1964), p. 110

Furthermore, Baker expressed the opinion that comfortable living conditions, little discrimination, and a good job opportunity prevailed more favorably for Negroes in the smaller cities of the North and West. Because of the higher social, educational, and job skill levels of the black migrants who arrived in Lansing between the late 1870s and 1914, a Negro community developed which was characterized by a larger proportion of home buyers, about 60 percent, and more prominent leaders than on might expect for the size of the black community. Jarvis supports the opinion that the early Negro residents were favorable accepted by the early whites. But white hostility began to increase a shown by the fact that black had experience greater opportunities within the white community prior to 1900 than available around World War I.

Prior to 1890 American Negroes labored primarily as agricultural or domestic service workers. Since most the black in the North lived in cities, they were chiefly employed in service occupations. Lansing particularly fitted this pattern because it was the capital and demanded hotel and other domestic services. The Negro, therefore, found ready employment.

The occupational structure of the Negro population changed little between 1850 and 1880. The primary male occupations were (1) waiters, porters, and cooks in the hotels and restaurants, (2) barbers, (3) house servants, and (4) common laborers. By 1880 there wer Negro brick masons and a blacksmith, foundry worker, janitor at the state house, furrier, and fish dealer. In some instances the Negroes owned their own businesses.

As the Negro population grew larger in Lansing, the female segment became more a part of the occupational structure. The women were employed in service occupations as servants, washwomen, and dressmakers. Young Negro women served as domestic servants in a number of white homes. The increasing number of employed black women resulted probably from the need to augment their husband’s earnings and the fact that the white women rarely entered domestic employment; there were, therefore job opportunities.

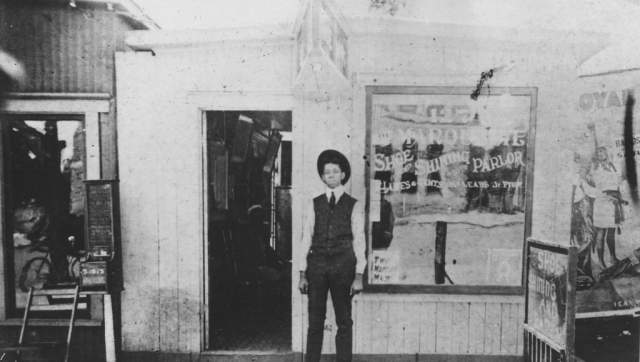

But as a permanent Negro settlement took roots, changes arose in the employment pattern of blacks. During the last two decades of the century blacks engaged in a greater variety of jobs, even though service occupations and common laborers continued to dominate. By 1894 there were eight teamsters, a blacksmith, four dressmakers, eight painter and paper hangers, five plasterers, nine stone and brick masons, five carpenters, two moulders, a teach, two nurses, and a clerk. A number of black-owned businesses operated in Lansing between 1880 and 1914; as many as five barber shops---seventeen barbers in 1894---two restaurants, a fish dealer, a blacksmith, a house mover, and three building contractors. Some of the businesses existed in the present central business district of Lansing on both Michigan and Washington avenues. Two of the building contractors, John W. Allen and Andrew Dungey, were noted for their excellent work in the construction of quality homes and buildings. Dungey built over 300 homes in Lansing.

By 1910 male Negroes found their occupational structure rather rigid. Little change had occurred after 1894, as they continued to predominate in unskilled labor, primarily general laborers, and service jobs, especially barbers and janitors. Because three black builders operated in Lansing, it probably benefited the existence of the Negro skilled craftsmen, especially carpenters, and brick and stone masons. The state government employed a few Negro clerks and janitors. The automobile and related industries, particularly foundries, boomed in Lansing during the first decade of the century. And about 10 percent of the employed male blacks gained a foothold as unskilled and semi-skilled workers. Domestic and service occupations accounted for 83.7 percent of the Negro females’ employment in 1910. About half of all the black women employed were servants. And the above Negro occupation pattern for both men and women generally persisted for the next forty years.

In conclusion, the major areas which repeatedly contributed to the growth and formation of Lansing’s black community before World War I were Michigan, New York, Indiana, Ohio, Virginia, Kentucky, and Canada. The primary Negro migration pattern represented intra-state movement within Michigan. A second stream involved a transfer from Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio northward into Lansing. The third movement extended westward from New York and Virginia, though one also spread westward from Ontario, Canada. All four of the migration streams became very distinct beginning in the 1870s. The exception to the usual Northern pattern concerned the shirt of Negroes from Canada into Michigan between 1870 and 1914 with the peak reached by 1894. And the historical roots of Lansing’s permanent Negro community lie particularly with those families which had settled for a time in Cass County, Michigan, before moving to the capital.

When the Negro population was small and immigration to Lansing slow prior to 1914, the total community could integrate new black arrivals. As a result, the initial residential patterns which evolve with the Negro settlement in the 1880s witnessed little change until after World War I. Negroes dispersed throughout the area of the city within the bend of the Grand River, but south of Ionia Street. Generally a few black resided in clusters in racially mixed blocks and a few additional clusters could easily accommodate the population increase. This study suggests that the constraints or exclusions imposed by the white majority prior to World War I were primarily directed toward a rigid occupation structure, rather than a segregated residential structure. Whereas, the latter developed during World War II when rigid boundaries imposed an involuntary choice of housing on the Negro, resulting in ghetto concentrations in west-central Lansing.

Notable African Americans Under the Dome

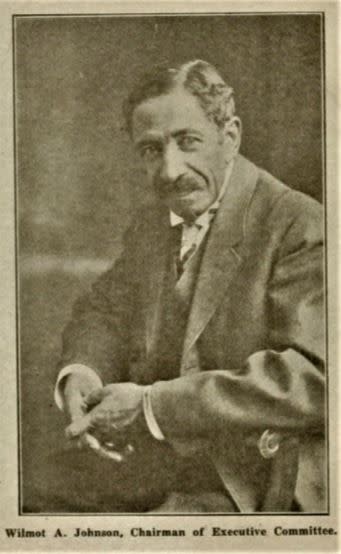

In 1915, longtime Capitol clerk Wilmot Johnson served as chairman of the Michigan delegation at the Lincoln Jubilee, a celebration of the 50-year anniversary of the emancipation of enslaved African Americans.

Johnson and the other delegates staffed a Michigan exhibit at the event in Chicago and published the “Michigan Manual of Freedman’s Progress,” which shared the accomplishments of Michigan’s prominent Black citizens.

We’re always learning more about the flags in the Capitol Battle Flag collection and slowly, #mistatecapitol staff are compiling histories of each of Michigan’s #CivilWar regiments. The latest addition to our regimental series is the 102nd Regiment U.S. Colored Troops. First organized in 1864, the soldiers of the 102nd initially served on picket duty, but quickly became involved in combat. At the battle of Honey Hill, a correspondent reported that the 102nd, “fought with the greatest determination of any troops on the ground.” Learn more about the men of the 102nd on our website.

Facebook post from Michigan State Capitol (https://www.facebook.com/MIStateCapitol)